Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

31 October 2025

Quite a lot has been written and said throughout history about challenging systems. And even in recent times, there has been a lot of system criticism in Norwegian media. Not surprisingly, there is a growing realisation that the status quo does not necessarily work particularly well. So the question, in a psychological sense, is why we agree to things that are not in our favour - especially in a democracy. It may not be a question of why those who profit from the status quo want to maintain the system, but it is more curious that those who suffer from the system also often choose to defend it rather than tear it down and create something better.

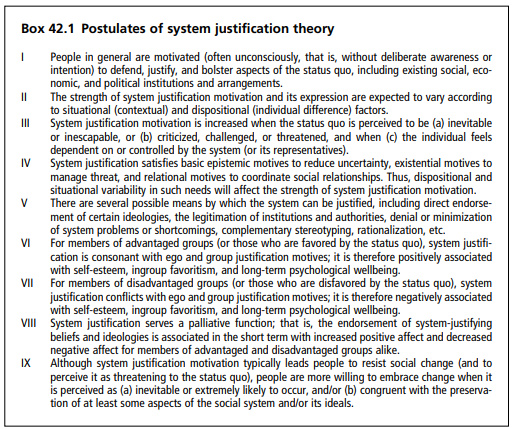

This remarkable phenomenon has been researched by social psychologist John Jost for about 30 years under the framework "System Justification Theory" (SJT). SJT is to be regarded as an umbrella theory or meta-theory, which in turn rests on a number of other well-known and well empirically supported theories in the field of psychology. There is also a good overlap with well-known philosophical and sociological concepts. There's a lot to explain, but I'll make an honourable attempt to tabloidise the idea here without losing too many important points.

To start with the very basics, systems in all shapes and forms provide us with a degree of predictability and a sense of community. No matter how objectively good or bad it is, it is something that groups us together and provides a number of norms and rules that help make the world feel less chaotic. It follows the good old English saying "better the devil you know than the devil you don't". Existentially speaking, there is something fundamental about it all.

In addition, SJT points out that it is psychologically easiest to think that the world is fundamentally fair, the so-called "just world fallacy". This is a mindset that contributes to a sense of security, and even when society is objectively considered unfair, it becomes psychologically easier to think that it is your own fault if something wrong happens because of the system - rather than thinking that the world is actually not working properly.

The latter in turn contributes heavily to reinforcing stereotypes and prejudices, both against oneself and others. According to both Kurt Lewin and Gordon Allport, it is easy to internalise prejudices, i.e. to feel a form of self-hatred, when you are treated badly by the system. Rather than going to the barricades and experiencing something akin to the French Revolution, you start to feel inadequate and bad for not making it in the current world order. Last but not least, part of the picture is that it also reinforces general stereotypes and prejudices against all deviant groups since the basic thesis is that "the system is right, ergo the problems we have in society must be due to the deviants" - whoever you have defined the "deviants" to be in a given context. Take your pick, history has enough current examples.

Also cognitive dissonance plays a central role here: If you're suddenly going to start embracing assumptions about the world that run counter to the beliefs you're bottled up on, named "one's world of assumptions" by Jerome Frank, it becomes a source of anxiety, stress and unease in the face of having to create a new, and perhaps fundamentally unsettling, view of the environment.

There are many more empirically solid traditions that also support the system's necessary maintenance - such as "Social Dominance Theory", tendency to follow authoritarian leaders, the desire to stand together in the face of existential threats ("Terror Management Theory") and more. I have previously described this in my articles, so just scroll back in the blog roll or look at Seema's websites.

And if you've got a bit of time on your hands, feel free to read the theoretical basis Jost puts forward about SJT (be the nerd you want to see in the world!).

In any case, the point is that the system is underpinned by a number of mechanisms that are very (!) difficult to break. The system, you could say, takes on an intrinsic value and demands to be maintained in a way that includes both those who benefit from it and those who suffer from it. Understanding SJT may not make it much easier to change the situation, but it may be a first step to becoming aware. In the worst case scenario, you can at least say "I told you so" when things aren't going so well.