Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

30 July 2025

Something you can see relatively often in the diversity field is that different claims are made with varying degrees of credibility. At the least relevant end of the spectrum are individual stories, often with a lot of emotion and little generalisability. At the more interesting end, you have studies where the inferential statistics are fairly consistent, so that you at least know that "there's probably a finding here".

But what is perhaps not so often emphasised is how vulnerable the very tools you use can make your research. Especially in social science research, where a lot of what we look at is based on batteries of questions, there is a lot that can go wrong. I remember a lecturer I had on the psychology programme highlighted this very well by explaining that psychology as a field of research often got a lot of grief (especially from the sciences) for "hiding a stone under a bush and then being very happy when they found the stone again". The metaphor describes the fact that, despite advanced statistical methods, research in "softer subjects" will often provide confirmatory answers to the questions you ask and the findings you are looking for. Or to put it in a popular way: "As you ask, you get answers".

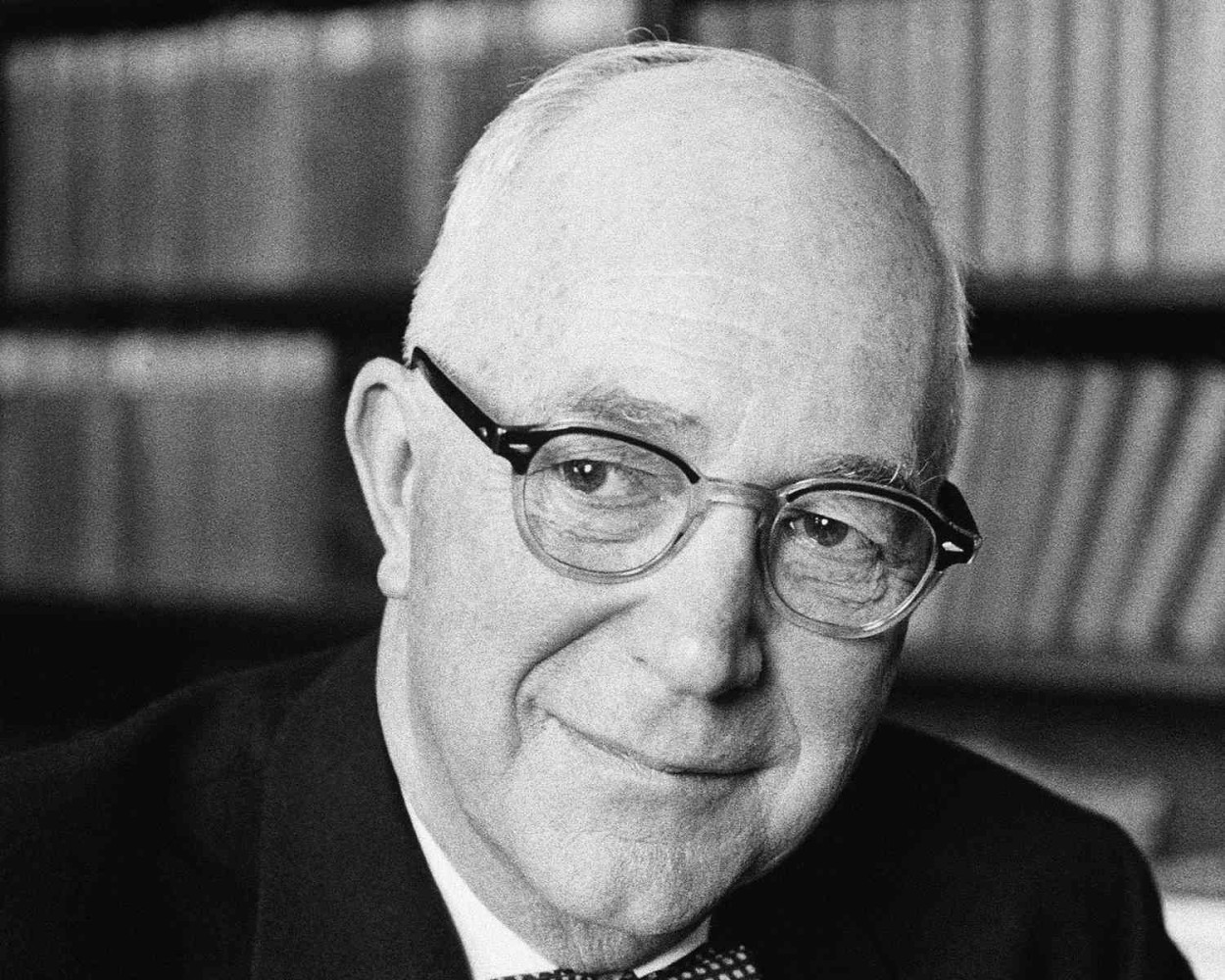

To take a concrete example, we can go back to the middle of the last century and look at the writings of Gordon Allport, perhaps the most important social psychologist in terms of defining the field of prejudice and discrimination.

As Allport points out, a survey was conducted in the USA where the question asked was "Do you think the Jews have too much power and influence in the United States?" (keep in mind that here we are 80 years back in time approximately). In this statement 50% of the respondents agreed. Does this mean that half of the population is anti-Semitic?

Well, it's not that simple. Remember that the question is leading and makes people think of a specific group in a specific context with a hint in the sentence itself about what is the "right" answer. Another survey asked instead "In your opinion, what religious, national, or racial groups are a menace to America?".

In comparison, only 10% spontaneously mentioned those of Jewish descent as a relevant answer to this question. So is 10% anti-Semitism the right proportion? Once again, it's a "yes" here. In a third study, respondents were given a list with the groups "Protestant", "Catholic", "Jewish" and "African American" listed and asked two questions:

- "Do you think any of these groups are getting more economic power anywhere in the United States than is good for the country?"

- "Do you think any of these groups are getting more political power anywhere in the United States than is good for the country?"

On the first question, 35% chose those of Jewish descent, and 20% did the same on the second. In short, you can roll the dice on whether anti-Semitism was at 10%, 20%, 35% or 50% in the samples you asked - or perhaps lean on the semantics you like best.

Even though modern social science methodology relies on a number of statistical tools to ensure the reliability and validity of questionnaires (and the same for tests that are not based on self-reporting), there is no getting away from the fact that the design of the tool by the researcher will largely define what the outcomes can be. In this respect, all users of research findings should also be good at reading scientific articles properly and seeing the logic applied in the light of other research, preferably also across disciplines (as when sociology, psychology and history make sense in context) and facets of their own discipline (as when self-reporting coincides with analyses of brain activity and/or behavioural studies in psychology).

And the example used above hopefully also shows in a simple way how diversity in particular can be very vulnerable to errors here.