Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

11 June 2025

Diversity research is a kind of continuous consideration of in-groups and out-groups, as well as how it affects being part of one or the other. But when it comes to organisational and team research in particular, it becomes very important to understand the concept of "fault lines". To start off light and easy with a solid definition of the term:

Fault lines are considered dividing lines within a group, splitting it into subgroups based on the alignment of multiple attributes.

If this feels like a mouthful, it's easy to say that fault lines is about how different you have to be before a social rift, a possible polarisation or problematic distance between groups actually occurs. This is one of the main points of intersectionality comes in: That is, the idea that you can have differences along several axes at the same time. For example, having a different age, a different sexual orientation and a different religion at the same time - compared to those you work with (diversity is always relative to context, as we've talked a lot about).

To take a simple and innocent example I usually use in courses: Imagine that a bunch of male entrepreneurs have been running a company for quite a while. They're now in their 50s and think they need to balance the gender balance, and at the same time bring in some updated knowledge to drive the company forward. So they hire a lot of female employees in their next recruitment round. Now gender becomes a new kind of difference in the office dynamic. But in addition, since they were looking for some new and fresh knowledge, there's a marked age difference here as well - perhaps several of the new hires are actually relatively recent graduates. So there are at least two things that separate the entrepreneurs from the new employees. In addition, recent research shows that young women tend to vote significantly further to the left than men (at least in today's society). So that's perhaps three clear dividing lines, and perhaps enough to create a slightly unfavourable atmosphere at the lunch table if you're not good at diversity management and constructive, welcoming conversations.

This is something we analyse for every single organisation we visit. It would be a little too easy to just assume that every type and amount of relative diversity has challenges at all times. As we always point out: "it depends". Otherwise, individual organisational analyses would be pointless.

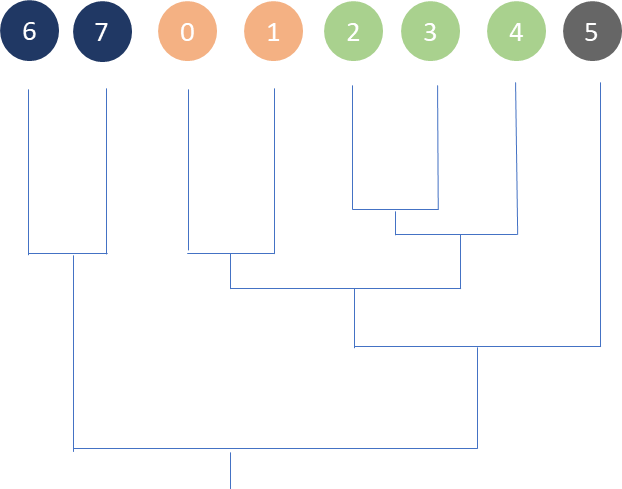

Take, for example, the cluster diagram below, which shows a fictitious example that could easily be a company we work with:

What we see here is that the response profile of the employees in the analysis creates clusters that belong together to a greater or lesser extent. In the image, we first see that "0" and "1" are close to each other and both coloured in orange. In practice, this means that it does not matter whether this organisation has a single degree of intersectionality, such as age, body type, neurodiversity, socioeconomic status, orientation or whatever it may be. They have a very similar way of responding (in the Diversity Index survey) to those who are not diverse, i.e. the majority.

But you can also see that when you have 2, 3 or 4 degrees of intersectionality, highlighted in green, you join a separate cluster that has a markedly different way of responding. Then we see that those with 5 degrees of intersectionality live alone as a separate group, and then those with 6 or 7 degrees of intersectionality have their own cluster.

With this type of analysis, we can give an indication of where fault lines run in an organisation, and the main point is, as mentioned, that challenges typically first arise when groupings are sufficiently different compared to each other.

In this respect, a lot of diversity research becomes a little oversimplified when you select different individual identities and emphasise aspects of these alone. Most often, both from our own figures and international research, it is a key point in organisations to know the degree of difference that creates different clusters, and what the distance between them is, in order to work on managing the range in a way that enables good well-being and optimal performance in the workplace. Not least, there are a number of relevant research interventions here, given that you recognise the problem and understand it.