Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

4 June 2025

By now, most people have probably heard of the so-called Dunning-Kruger effect, originally described by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999. The idea is simple: when you know little about a subject area, you often don't have the self-awareness to realise how little you actually know. As a result, you tend to overestimate how much you actually know about whatever it is.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is thus a result of what in psychology is often called metacognitive abilities: Our ability to see ourselves clearly in different contexts. I'm sure many of you have noticed that you have mastered this to varying degrees yourself (and seen the same in others). I remember we joked about this after the first year of psychology, where you go through everything from psychophysics to research methods to psychoanalysis during the first year, but at a very superficial level. You can be left with the feeling that "wow, now we've covered everything about the field, really". But then, not surprisingly, the illusion is shattered to pieces as you delve into brain anatomy, details of treatment research, measurement methods, situation-driven behavioural patterns, personality structures and a million other things that sometimes feel like being lifted off the pier with concrete shoes. Thus, after the first year, you might think that you are on what is humorously called the "Peak of Mount Stupid" in the graph below, before sliding down into the abyss and surfacing again at the "Plateau of Sustainability" after delivering your thesis several years later.

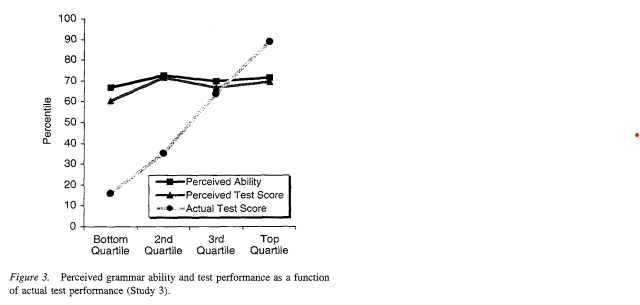

Unsurprisingly, the reality of performance in a field is also quite linearly related to competence, and those who have been at it for a long time have a much more correctly calibrated assumption about their own level of knowledge than those who are fresh. It looks something like this (one of many examples available):

Since this, as mentioned, is about metacognitive abilities, it's probably reasonable to assume that certain disciplines are more exposed to the effect than others (depending on how much it apparently requires of analytical effort, and thus one's own perception of difficulty). I remember a lecturer on the programme saying that debates in psychology with lay people can be difficult because everyone has their own brain, and therefore their own psychology. And then people tend to think that personal experiences and reasoning around these are actually the reality of empirical psychology. The truth is that many of our behaviours, emotions and thoughts come from completely different causes than what we intuitively believe - that's half the point of research in the field! But that's a hard pill to swallow as a supposed "expert on your own brain in your own life".

On the other side of the scale, I can mention that I lectured in statistical methods and algorithms in performance assessment. It is so difficult and obviously demanding for "System 2" reasoning (i.e. conscious analytical effort) that I think very few people, even after taking the exam, felt they really knew it. Even as a lecturer, I'm constantly wondering whether I've really understood it.

The bad thing is that diversity field is clearly closer to psychology in terms of people's assumptions about their own level of knowledge. It's terribly easy to gain a little knowledge and think "it's just a matter of time" - because large parts of the subject are "soft science" and thus not as obviously contradictory as, for example, science.

In reality, the field is an interdisciplinary swamp with elements from psychology, law, management development, statistics/data analysis, philosophy, sociology, social anthropology and so on. So I can't claim to know it all, but have to choose to comment on the parts of the subject I have expertise in, and let colleagues cover other parts of the puzzle. The consequence of that seems easybut in practice very complexmakes the whole thing particularly susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Yay...