Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

8 May 2025

To understand today's article, it's a good idea (!) to read my previous article about "Stereotype Content Model" (SCM). Otherwise, this is a bit left hanging in the air. The reason is that prejudice roughly follows exactly the same logic as stereotypes, but that removes the positive effects of stereotypes in practice. After all, as previously mentioned, stereotypes can have positive effects too, depending on the context. But prejudice not so much…

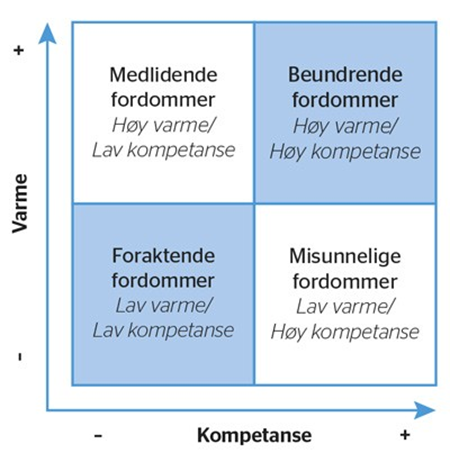

With SCM fresh in our minds, we can imagine that prejudices lie along the same axes as in the aforementioned model. But for the sake of simplicity, we divide them roughly into four categories of prejudice:

Now I'm going to be really lazy and simply include the explanation of the four quadrants from Bye (2015):

The admired. Several of the groups were seen as either competent and very warm (e.g. women, gay men and the middle class) or competent and quite warm (e.g. Norwegians, men, students and people with a high level of education). Overall, these groups can be thought of as representing the typical in-groups or reference groups in Norway, i.e. groups that many people either belong to, compare themselves to or want to be part of.

They disliked, but respected. Across countries, there is one social group that consistently ends up in the envious prejudice quadrant: rich people. Even in our data, rich people are recognised as competent, but we don't like them and consider them cold.

The kind, but not so skilful. There were few groups that clearly ended up in the compassionate prejudice quadrant; recognised as friendly but not respected as competent. The exceptions were disabled people and people with low education. Both of these groups can be said to face this shading of prejudice.

The despised. The participants' responses showed that three groups are stereotypically regarded as cold and incompetent: drug addicts, beggars and Roma. This gives a clear picture of who is not included in the larger "we". Poor people, those on benefits and the unemployed were also considered incompetent, but were rated more favourably on warmth.

Those in the centre. Some groups were ranked in the centre of both the heat axis and the competence axis. This applied to immigrants, for example. When, in the final part of the survey, we asked participants to rate specific immigrant groups, we saw that Polish, Pakistani and Iraqi immigrants remained in this centre position. Swedish and Somali immigrants, on the other hand, were placed in diametrically opposed positions, distinguishing themselves from the general "immigrant" category and the other immigrant groups. Swedish immigrants are stereotyped as Norwegians (i.e. warm and competent), while Somali immigrants share the clearly negative (low warmth, low competence) stereotype of beggars, Roma and drug addicts.

A lot has certainly happened in Norwegian society since Bye published the article referred to here (2015). Both which groups we consider relevant in society and how we assess them are constantly changing over time (and between cultures).

What seems to have been a development, or at least a possible hypothesis, is that diversity in some sense very often seems to have been placed in the "nice but not so talented" quadrant in recent years. From what you see in the media, and even from narratives among those working with DEI, the idea often seems to be that those with diversity primary are in need of help. Even though this is very well-intentioned, such a way of thinking and talking overshadows the fact that diversity is a resource. And a necessary part of our working life. When we've measured that 45% consider themselves at least one type of diverse across more than 6,000 data points, it's odd to focus mostly on compassion as the driver of work here.

It also seems that quite a few of those who represent diversity have spoken out in this context. There have been several statements indicating that many are tired of being "a strong story" or "a great inspiration" - the primary desire is rather to be seen as equal and relevant as a colleague. After all, that's the big problem with "the nice, but not so skilful": You want to be nice to them, but such an attitude quickly stops you taking them seriously as a leader, a subject matter expert, a talent and so on - everything that lies on competence axis.

In any case, the consequence of understanding the bias categories should probably be to become better at reality calibration with the person you are dealing with. As always, the problem arises when we don't stop and investigate, thereby allowing various preconceptions to play out unhindered.