Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

23 April 2025

I think I should start by pointing out that stereotypes are a consequence of our highly necessary habit of categorising each other as people. Even though the term stereotyping often used in a negative sense in today's society, in purely psychological terms it is merely an association we have with groups of people. And these associations can be positive, neutral or negative. What's more, they often vary greatly depending on the context. Being part of a group, for example "the elderly", will confer higher or lower status depending on the culture in which you live (i.e. "the elderly"): Are we in a youth-glorifying culture or one that has a high respect for life lived?).

Although different types of group affiliation produce different results, the basis for our judgement is the same regardless - it is based on a number of tendencies that have been important throughout the course of evolution. Like when the so-called "Stereotype Content Model (SCM) points out, we're really trying to find out two things when assessing other people: a) the extent to which people are warm (tolerant, honest, pleasant, etc.), and b) the extent to which people are competent (intelligent, competent, confident, etc.).

As Wikipedia in this case says very well:

"The model is based on the notion that people are evolutionarily predisposed to first assess a stranger's intent to either harm or help them (warmth dimension) and second to judge the stranger's capacity to act on that perceived intention (competence dimension)."

So, as I like to point out when I give courses, by and large the way we talk about others is really moving a point around in a two-dimensional space. We use an awful lot of adjectives when talking about different people/groups of people, but it's largely just a droning on about whether someone is an axe murderer or a new bestie, and whether they can barely find their backside with a torch or manage to get things done. To put it bluntly.

And the reason why we use group information to judge people is simply an information scarcity problem: When we meet someone, we start with what (little) we know to try to figure things out. But over time, with an individual where we get more and more information and build a relationship, the need to use identity for judgement will disappear.

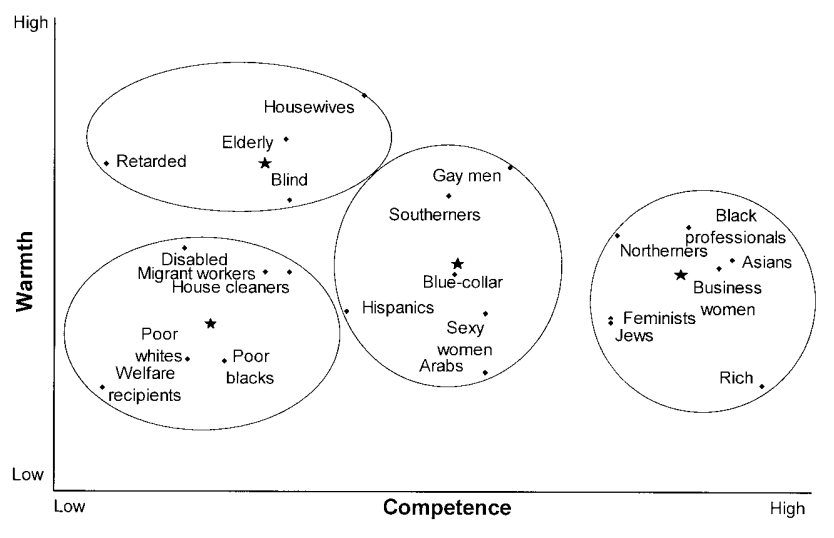

To illustrate the point, we can look at an early SCM from 2002, where the researchers assessed a number of groups they had surveyed in the USA (the selection of groups came from a preliminary study where they in practice asked people what they considered to be relevant groups in society - There is therefore no reason to criticise the researchers themselves for their choice of groups and their names):

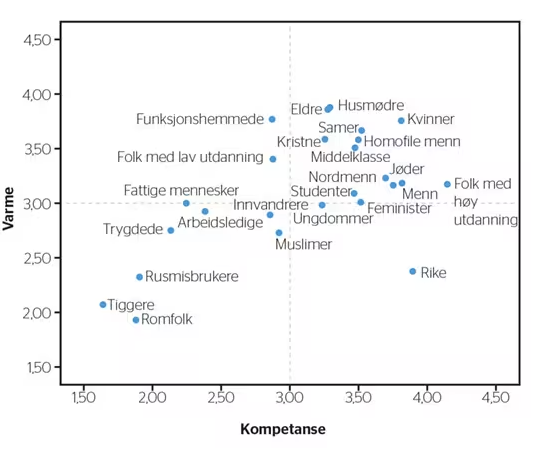

As mentioned, the assessment of different group affiliations, and not least which groups we consider to be relevant, will vary from place to place and across time. In Norway, the following model was validated in 2015, and as you can see, it is different from the American model:

I'll come back to the consequences of being put into the different degrees of warmth and competence in a later article. But for now, it's a good idea to simply note that when we assess others based on categories, it's just an attempt to find out some basic essentials before we get the full information (as mentioned, stereotypes are only relevant before a real relationship is present). Keeping this in mind when involved in the diversity profession is naturally quite important and also helps to understand your own and others' thought process. Life becomes easier when you understand what people are trying to consider in their descriptions of other people.

For example, let's assume a new employee named Arne, where others are talking about him: "Arne didn't bother coming to the team building last week - I think that's bad form" (downgrading warmth). Then someone else might respond "Hey, I heard it was because he had to take care of his sick wife" (upgrading warmth). Then "But wasn't he also late for the developer meeting last week and hardly contributed?" (downgrades competence). "Yes, but that was because he was up all night fixing a bug that crashed our system" (upgrades competence, and maybe also warmth). And so on. Without using group identity as a starting point, you can hopefully see the progression of increasing information available and then the movement of the point in the two-dimensional space.

Not least, this understanding enables you to correct yourself when you go astray. Because this is only what people think about others - not a measure of what is real in a given case. When you're aware of what you're doing, you can also catch yourself in it to a greater extent.