Jakob Sverre Løvstad

CTO, Seema

14 May 2025

A common question when we talk about diversity and different groups is, in a way, "what is the truth?". In a field (and a society?) often characterised by a lot of emotions, it can be a little easy to trudge off in a direction in your head that is not entirely rational. So a slightly more grounded understanding of what the fundamental issue is can be helpful.

In a nutshell, there are two factors that determine how a person does in life: cognitive abilities (i.e. intelligence) and personality (often measured with a validated tool such as the NEO-PI/Big Five). This is perhaps not so surprising. After all, intelligence measures how well the brain processes information, and is tested by measuring attention, abstraction ability, short-term memory (some like to include long-term memory too), logical processing, how quickly the brain works and so on. You can also add tests that shed light on other types of reasoning if you really want to go full nerd in neuropsychology. In all cases, it is the basis for solving all of life's problems in a better or worse way.

Personality is about things like how extroverted/introverted you are, how compassionate, how open to new experiences, how anxious/nervous, how conscientious and so on. It's no wonder that it has a lot to say. If you tend to wet yourself in the face of challenges, or don't have the ability to complete tasks, never say anything or whatever, it will naturally affect how things go in many situations. To put it bluntly, of course. Often, the NEO-PI/Big Five is what's used since this is the best validated scale (as opposed to the Myers-Briggs nonsense which is really just something Tinder feels is relevant).

For those interested, Robert Plomin's book "Blue Print" can be a very easy introduction to the thinking and some of the research behind it.

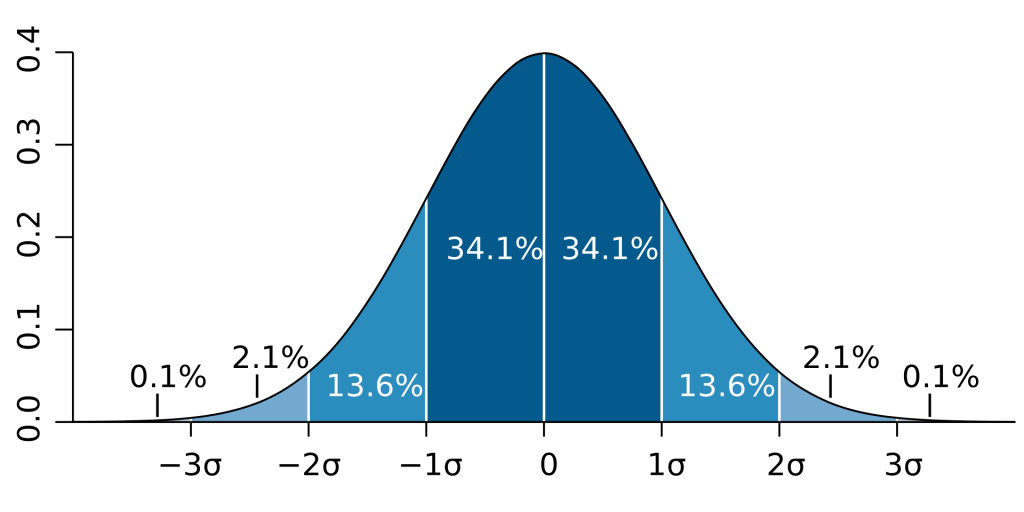

When it comes to different groups often categorised as diversity, the "truth" is that personality and intelligence are normally distributed. That is, some are the next potential Albert Einstein or Rosalind Parks, and some are the next village idiot, but the vast majority are in the middle of the tree. And some are super cosy, others are axe murderers - most are "just okay to keep up with". Some have extreme follow-through, others barely know what tasks they should be doing - most "make an adequate effort at work". You get the idea. What may skew the distribution are groups consistently exposed to extreme neglect, poor prenatal conditions or nutritional deficiencies, but that will be a separate article if necessary. And there are some differences across genders, but they're not gigantic effect sizes (also something that will have to be addressed separately one day when I have time).

Not least, we see that various psychopathologies and problematic personality traits are also fairly evenly distributed. It is by no means the case that gender, orientation, political affiliation, body type, religion or whatever makes you a better or worse person, or more/less disturbed. It may be that the very expression of underlying vulnerability (the so-called p-factor, for those who want to read more) come out in different ways due to external assumptions, but the statistic remains that we "all suck about the same amount", regardless of the diversity we belong to, or not.

The fundamental problem alluded to originally, however, is that perceptions of different groups not is informed by the above understanding. Again, you should have skimmed through previous articles on "Social Content Model (SCM) and prejudices, where I highlight the fact that our perception of others does not follow normal distribution logic. In this regard, we often warn in our lectures about what are called "single stories" (simply sounds better in English): The stories we tell ourselves about others based on grouping, and which are a source of many challenges.

Such stories tend to be unsophisticated and emotionally powerful. The road is short to some form of judgement (hence "prejudice"). And there is often a lot of morality involved ("we are the good guys, the others are morally reprehensible") when something becomes particularly inflammatory. Think back to the heat axis in SCM. From an evolutionary point of view, it's all very understandable, but there are quite a few glaring examples of how this goes wrong, including in Norway. Perhaps even at times especially in Norway where we have a culture of the world leader in social control.

On the other hand, we also have groups that have an undeservedly good reputation. For example, there are women, Sami, middle class and gay men high on both axes in Bye (2015) see article about SCM. Of course, this is just as much rubbish as when we make negative assumptions. There are just as many nasty, crazy and unhelpful individuals in the aforementioned groups as elsewhere, so there's no point in overestimating.

Once again, I would like to encourage you to explore alternative narratives, to calibrate reality on an ongoing basis. When you hear a story about a group or an individual that is emotionally charged (typically follows thought bias), it's good to stop and think what the other side of the story might be. Are we entering an accepted social narrative as "default", or are we thinking factually? What evidence is there one way or the other? Are there other factors that are causing this than what you think? And so on. The frontal lobe must be activated so as not to get lost.

...as a small, but important, PS at the end: Remember that selection can actually mess with the entire normal distribution logic. If you manage to recruit only "the cool and smart ladies" into an organisation, the positive bias mentioned earlier will be true. And if we look at the groups in the least well-off quadrant, we also find those that are largely selected downwards in terms of definition (for example, the ethic "Substance abuser" is a definition that carries with it a great deal of selection). Similarly, "People with a high level of education" will be a definitional selection in a positive direction. This is a bit obvious, but it's good to emphasise in conclusion for the sake of clarity.